- Strawhacker emphasizes the importance of parent involvement in the process: “When parents partner with the team, it is an amazing combination. Parents know their child better than anyone. They can tell us everything to watch out for and how their child manifests things like low blood sugar. Do they have an aura prior to a seizure? How do they respond in stressful situations? How do we calm them? They are a wealth of information. We come in as professionals with a wealth of education and experience. Together, we make the best plan possible.”

For a more in-depth explanation of these steps, check out this guide from NASN. If you’re wondering what an IHP might look like, here are sample IHPs for seizures and asthma. Remember, these are bare-bones examples; a real IHP will be much more personalized, in-depth, and meaningful.

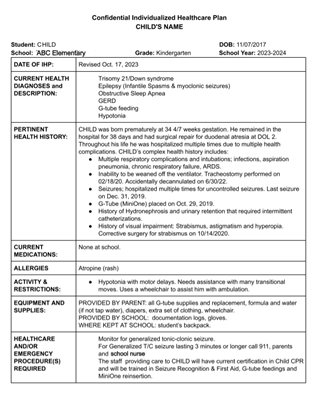

One Undivided parent shared their child's IHP with us (identifying information redacted) so you can see an example school health plan:

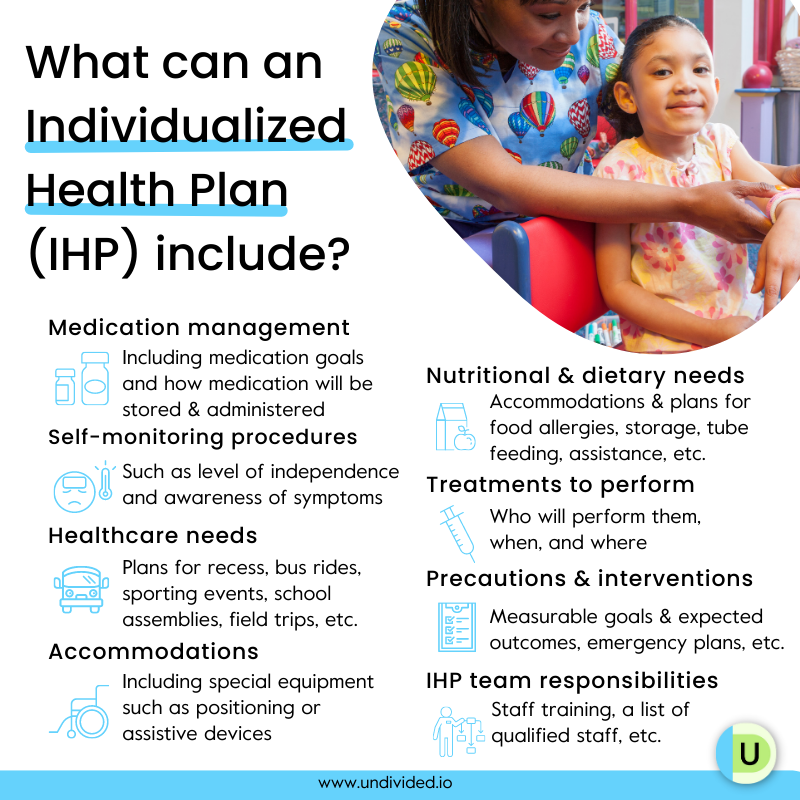

Some things you may see in an IHP

Every IHP is unique — some IHPs may cover a few of the following items while others may cover all of them, and more. But it’s important to note how expansive and detailed an IHP can be, and how many different health needs it can address.

Your child’s IHP may include:

- A list of medical triggers

- Self-monitoring procedures (such as level of independence and awareness of symptoms)

- Healthcare needs at school (plans for recess, bus rides, extracurricular activities, field trips, etc. )

- Precautions and interventions (measurable goals and expected outcomes, treatment interventions, emergency plans, who will be responsible if the nurse is not available to respond, etc.)

- Special considerations (such as a field trip plan, extracurricular activity plan, assembly plan, etc.)

- Nutritional and dietary needs (accommodations and plan for food allergies; how food will be stored; precautions for situations such as forgotten lunches, evacuations, and emergencies; feeding plan such as safely handling tube feeding; instructions for assistance during mealtime, etc.)

- Treatments to perform (who will perform them, when, and where) Medication management (how medication will be administered; where the medication will be stored and accessed; medication plans for field trips and emergencies; medication goals; self-monitoring and reporting potential side effects to the parent and school nurse; etc.)

- Accommodations such as special equipment, positioning, or assistive devices

- IHP team responsibilities (staff training, a list of qualified staff, etc.)

Should an IHP be part of an IEP or 504 plan, or can it be a stand-alone document?

You don’t need an IEP or 504 plan to have an IHP, but it is highly recommended. A stand-alone IHP might be okay if your child’s health needs are extremely minimal. Conversely, while health needs can also be addressed in an IEP or 504 plan, it’s usually recommended to have an IHP in addition to an IEP or 504 plan because an IHP is the one document that centers everything health-related. In this clip, Strawhacker explains how IHPs relate to IEPs and 504 plans:

An IHP can be attached to the IEP or 504 plan (depending on state law), or it can be a separate document referenced by the IEP/504 team. However, because an IHP contains school-related nursing and health services, it is included in the IEP in the related services section under supplementary aids and services. In a 504 plan, the IHP would be referenced as part of the student’s health accommodations.

Now, let’s explore the legal reason why an IHP should be part of the IEP or 504 plan: IHPs are not legally binding documents that come with legal protections or procedural safeguards and protections for families (which IEPs and 504 plans do). Because IDEA doesn’t apply with a stand-alone IHP, there's no obligation to provide FAPE and no legal means for parents who disagree with the healthcare plan to challenge it.

Education advocate Lisa Carey gives some advice on why to incorporate a health plan into an IEP, including real-world examples.

Can my doctor write the health plan for my IEP team?

While information from a child’s physician is paramount to the school nurse who is writing the IHP, doctors don’t have the authority the school nurse does in a school environment and can’t write the IHP themselves. They should, however, provide the nurse with the necessary medical information needed for the IHP.

Health care and health planning in a school setting fall under the scope of the school nurse and require knowledge of the school environment that a physician doesn’t have, including specific accommodations and modifications or school programs.

In this clip, Strawhacker details what you need to know about a physician or primary care provider’s role when it comes to IHPs:

Will the school treat my child’s medical information confidentially?

Providing medical information to the school may feel like an intrusion or invasion of privacy, but making sure the nurse knows your child’s unique needs is crucial to personalizing care. As Strawhacker reminds us, every child is unique, even if they have the same diagnosis:

Strawhacker says that everything a nurse receives is treated confidentially as part of the Nursing Practice Act and FERPA (Federal Educational Records Privacy Act); this includes information they store online and in paper copies. Health information in the educational setting is regulated under FERPA but may need to be accessed by those who are involved in your child’s day-to-day activities at school, such as the teacher, bus driver, or administrative staff. This is listed as “legitimate educational interest” in 34 CFR Part 99 of FERPA.

She explains, “For FERPA, I can share that information with anybody who requires that knowledge in order to do planning. It's not like that information is going to stay with the nurse. It probably is going to be shared in bits and pieces as needed to maybe include an accommodation or to include a modification for special education, maybe a shortened school day. All of those things are managed by the school nurse when it comes to those records, or the occupational therapist or the physical therapist or the speech and language pathologist, whoever it is that has those records. We’re very protective.”

What happens if the nurse wants to include information in the health plan that my child would like to keep private from their teachers?

Our kiddos have a lot on their minds when it comes to school, whether it’s academics, friendships, or growing up in general. Health can be a sensitive topic, and it’s understandable if they express the desire to keep their health information from specific school officials, including their teachers. The sharing of information is usually on a “need to know” basis and falls under FERPA’s “legitimate educational interest.” This means that the information will be shared with the teacher if the teacher needs it in order to fulfill their professional responsibility.

But who has access to that information should always be a discussion between the nurse and the family. In this clip, Strawhacker gives us some examples of information sharing and explains why it is critical:

What can I do if I disagree with the nurse’s plan?

Any disagreement should be addressed with the nurse who is writing the IHP, as well as the IEP or the 504 team, if the plan is a part of an IEP or 504 plan. Strawhacker explains why:

When the IHP is part of the IEP or 504 plan, you can challenge the IEP or 504 plan in the usual means. Strawhacker tells us that “because an individual health plan outlines services that are provided — nursing services — it is part of the IEP” and parents can file for due process if they object to the services being provided in the IEP. “I have had parents file for due process when they object to the services being provided within the IEP,” Strawhacker says. “I've had really good luck with mediation where the school and the family come in and we talk about very hard things and try to come to something that’s agreeable to everyone and that we know gives the child what they need through their IEP.”

What happens if my school doesn’t have a dedicated nurse on site?

Education advocate Lisa Carey explains that a school nurse, like other related service providers, may cover multiple schools. Even if there isn’t a full-time nurse onsite, all public schools have a nurse assigned to them. Strawhacker tells us that this nurse is available on call and is responsible for performing all duties required of a registered school nurse. When an IHP is required, the assigned nurse will perform the steps of the nursing process, train staff, and provide supervision for those tasks that can be delegated. If a student needs immediate access to nursing assessment or judgment, the team should consider whether or not the student may require a 1:1 nurse instead of a trained paraprofessional to support their health needs.

When do I need a school emergency care plan? Who should review it?

An emergency care plan (ECP) is developed by the school nurse (with medical information provided by the parent and physician) and is considered an intervention as part of an IHP. Strawhacker tells us that an emergency care plan tackles anything that might happen at school that “needs to be handled in a special kind of way.” For example, if a child has seizures and needs nasal midazolam to be administered within three minutes of seizure onset, an ECP can address that. An ECP isn’t needed if an emergency can only be solved by calling 911 because that’s what anybody would do in an emergency.

An ECP is also specific to the school setting, Strawhacker says. “If the student is having a seizure, who calls the nurse to respond? Who then is going to determine whether to call 911? When 911 arrives, what door do they come to? Who’s going to escort them through? It’s all of those details that can really make or break a situation. And that’s why it’s so critical to outline for the school how that’s going to happen. A seizure action plan gives you some details, but it’s not the be-all, end-all. And that’s why it’s critical to have a school nurse in every building every day, to be able to write out those plans, implement those plans, and provide quality care.”

What happens if my child needs to take medication while at school, on a field trip, or during a drill or emergency evacuation?

A professional nurse is responsible for all nursing services in the school, including medication administration and management. If your child needs to take medication at school, and is learning to self-manage their medication, the IHP should clarify important aspects of medication monitoring, including how medication will be administered, how the student’s health status will be monitored, where the medication will be stored and accessed, the location where care will be provided, and who will be providing the care. The IHP will also include medication plans for field trips and emergencies in addition to medication goals, such as your child working toward self-monitoring and reporting potential side effects to the parent and school nurse.

In this clip, Strawhacker discusses the importance of medication monitoring:

When it comes to special circumstances, such as field trips or emergencies, there must be extra planning to make sure that your child’s needs are being met. While an emergency care plan isn’t the same as an emergency evacuation plan, it’s a good idea to make sure your IEP or 504 plan has an emergency plan specific to the medications or other supports a child might need to have with them during an emergency evacuation or a shelter in place.

In this clip, Strawhacker discusses how a nurse plans to meet medical needs on field trips, on the school bus, and during evacuations:

How do I know if my child needs a health plan?

While the more common conditions that might require an IHP include allergies, asthma, seizures, and diabetes, any health condition that requires ongoing nursing services at school should have an IHP, even those you may not consider a health condition or disability. These include Celiac disease, bowel and bladder problems, immunodeficiency, tube feeding, migraines, brain injury, ADHD, and mental health (anxiety, depression, PTSD, etc.).

A health plan can also address safety. Carey explains how a health plan can be a great way to address medical safety concerns you may have, and get your child a 1:1 aide or nurse, if appropriate.

Another situation to consider is when your child is temporarily immunosuppressed, hospitalized, or has a long-term illness but is well enough to attend school. In this case, an IHP opens up many options and opportunities. Every child has the right to attend school and receive a free, appropriate public education (FAPE), whether they have special healthcare needs or not, and IHPs, IEPs, and 504 plans work together to help them attend school and maintain their health safely — with a plan in hand!

Where do I start to make a school health plan for my child?

Now that you know what an IHP is, let’s talk about how you can start creating one. If you already know that your child requires an IHP, reach out to the school and ask who the point of contact is. While an IHP can be written anytime during the school year, we recommend starting this process as soon as school starts in the fall. If the condition(s) is complex, please alert the school as soon as administrators are available, usually in August. This allows time for the school to prepare.

Once you have your contact(s) (usually the school nurse), request a meeting to talk about your child’s health care needs and ask questions about the plans and policies the school already has in place. Before the meeting, make sure you’ve done your own research and documented what services and accommodations you feel your child requires. At the meeting, share your notes, including documents from doctors and care providers. The school nurse will then make a determination about how an IHP can meet the health needs of your child and start the process of creating one.

You know your child better than anyone and are an important member of their health team, so advocate and ask as many questions as you can. You can also contact your child’s teacher(s) prior to the school year starting to discuss the IHP and/or IEP/504 plan. This mom shares how she made a PowerPoint presentation on Celiac disease for her child’s teachers, including examples of gluten-free snacks as well as school supplies that may pose a risk for her child, such as Play-Doh and macaroni necklaces.

This is just one example of how communication is key when creating an IHP. Remember, IHP planning and evaluation should be ongoing, especially as you track your child’s progress toward their goals such as developing self-care, self-advocacy, and self-assessment skills.

“It should not be just once a year, and it should not be, ‘we want the records and we don’t care what you have to say,’” Strawhacker tells us. “Parents have so much valuable information — it is an ongoing partnership. And ideally, what we’re doing is creating a scaffolding, a foundation, a safety net, for that student at school. It’s critical to have that conversation. It becomes especially important when we have things like high school, extracurricular activities, out-of-state field trips, etc.”